How to estimate velocity in Scrum to escape the feature factory

Poker Planning is a collaborative game… that developers often lose! Here are the original fair rules that will provide developers time for technical work.

Some teams are somewhat experienced in Agile & DevOps (but mostly from the cadence & ceremonies perspective)

The team uses sprint planning and velocity by the book, yet they never have time to work on technical excellence!

Technical excellence, the practice of improving the structure of the code by doing continuous refactoring is completely foreign to most developers, who are being told that if they are good at what they are doing, they should be able to do it correctly on the first try.

We get messier code, more complicated maintenance, and an unsustainable rhythm without enough technical work. But, unfortunately, non-technical people are usually not aware of the importance of technical practices.

I said in the previous post that running planning poker sessions can help us here. The idea is to plan as many story points for the next sprint as delivered during the previous one. This will accommodate variability and create time to catch up on technical debt.

The number of story points delivered per sprint is the Velocity. Unfortunately, the general recommendation about estimating velocity in Scrum is terrible! As a result, many Scrum teams over-commit and skip important long-term technical work. That’s how agile feature factories are born!

Did you know that developers would get time for technical excellence by forecasting just as many story points as delivered during ONLY the previous sprint?

Let’s see how to leverage Scrum Velocity to reach a sustainable and effective pace.

- The typical (but flawed) way to estimate the velocity

- What’s the problem with averaging velocity?

- Just use the previous sprint to estimate velocity!

- It’s not that easy, though!

The typical (but flawed) way to estimate the velocity

Add up the total of story points completed from each sprint, then divide by the number of sprints. (Google answer’s to “How to compute velocity scrum”)

What’s the problem with averaging velocity?

A classic situation

A few years ago, I worked with a team facing delivery difficulties. Here is what I noted about its sprints and velocity:

- The amount of story points the team delivered (its velocity) varied a lot from sprint to sprint.

- Yet, the team members were doing anything they could to deliver what they had planned:

- They were working full-throttle on stories right till the end of the sprint.

- Things turned out well from time to time, and they would manage to finish before the end of the sprint. They would then catch up on what they had not delivered on previous sprints.

- As a result of all these efforts, the team members were exhausted.

- They were also aware that they were pilling up technical debt.

- Unfortunately, the situation looked to be getting worse!

I guess you can relate to this story: most of the teams I have worked with have been in this situation!

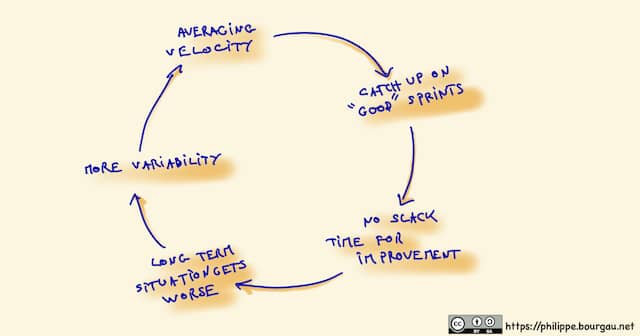

The vicious circle of averaging velocity

Let’s see what happens when we use the average velocity in the previous situation.

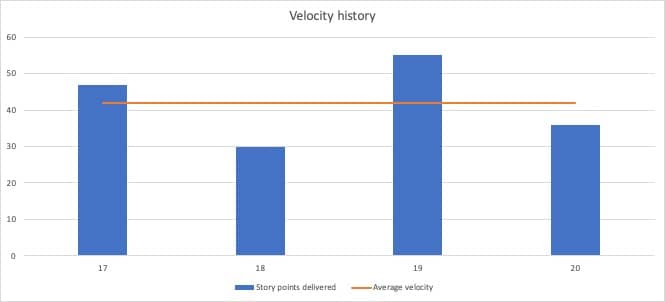

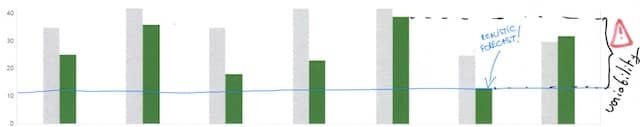

Here is a sample velocity history:

The average velocity over the 4 previous sprints is 42. Let’s assume that the team now plans to deliver this average: 42 story points. During these 4 previous sprints, the team produced:

- more than 42 story points twice

- less than 42 story points twice

If the team does not change anything else in its way of working, history will repeat itself! So here is what we can expect over the following sprints:

- The team will not deliver what they planned on half of the sprints. This will generate stress for everyone and degrade trust with business stakeholders.

- On the other half of the sprints, the team will manage to deliver what they said. But team members are likely to start catching up on what they did not tackle in previous sprints! Unfortunately, from the eyes of business stakeholders, it’s only late payback!

In the end, the team is in a constant state of catching up. This constant struggle to meet the plan makes:

- The team look unreliable and non-trustworthy in the eyes of business stakeholders

- The team members cut corners and take technical debt

- The team members work under permanent stress

In fact, averaging velocity does not change anything to the previous situation! On the contrary, it degrades trust, generates stress, and pill-up technical debt.

Why are people averaging velocity?

The only, conscious or unconscious, reason to average the velocity is to game the metrics! The team can show a ‘predictable’ face by communicating about the average.

Unfortunately, this strategy does not address the root causes of the variability. Instead, it only makes things worse.

Averaging the velocity makes everything looks ‘green’ from the outside, while the situation is still ‘red’ inside, like a watermelon.

Just use the previous sprint to estimate velocity!

Let’s resume the story about the team I mentioned above. The team needed to plan less per sprint. Fortunately, the organization had a goal to increase “predictability.” The team could leverage this to reduce what it planned every sprint. This picture shows how we cut the planned velocity:

This was a hard cut to swallow, but the team soon had time for new activities:

- pair and mob programming

- pairing between the different profiles in the team to increase generalist skills

- investing in a test framework to increase coverage of legacy code

- taking more time to write clean code

- investing in documenting some critical but forgotten parts of the codebase

After a few sprints, stakeholders noticed that the team was getting in control. In addition, limiting the planned work had kicked off a continuous improvement mindset in the team. As a result, the team member’s mood improved significantly in a handful of weeks!

How to calculate velocity and capacity in Scrum

Here is how the literature tells us to calculate velocity and capacity in Scrum:

To predict your next iteration’s velocity, add the estimates of the stories that were “done done” in the previous iteration. (James Shore in The Art of Agile Development, 1st Edition’s)

It’s that simple! Over a few sprints, the team will reach a velocity close to the minimum in their sprint history. If the team already has its history, it could start with this minimum. Here is what happens with this strategy:

- The team will deliver what it planned in 95% of the sprints. This builds trust with business stakeholders and reduces stress.

- The product owner will be able to predict what the team can deliver.

- Sometimes, the team will finish its stories before the end of the sprint. The team members will have some time to refactor, test, or tackle other significant improvements. This addresses the root causes of variability. It makes work more sustainable and less stressful for everyone in the long term.

- As continuous improvement compounds, the productivity of the team will also increase. The team will increase what it can deliver every sprint in the long run. Again, this will build trust with business stakeholders.

In the long term, this strategy beats averaging velocity in all aspects. Not only for developers but for business stakeholders too!

It’s not that easy, though!

Even if we know things will be better in the long term, getting there, though, is tricky. At first, it will deliver less than the ‘Run As Fast As You Can’ strategy.

Here are the main challenges the team will have to overcome.

Negotiating the change with the Product Owner

This “long-term” strategy stresses the product owner’s duty of excluding what not to do!

Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential. (The Agile Manifesto Principles)

Some product owners will push back! As coaches, we can help by training and preparing the team to negotiate. We can also facilitate the discussion to turn it into constructive brainstorming.

Parkinson’s Law

Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. (Wikipedia)

Unfortunately, Parkingson’s Law is real! As coaches, we can help by adding visibility. For example, we can show the Scrum Master how to track the day of the sprint when all the stories are closed.

Scope Creep

Developers will start new user stories when everything planned for the sprint is done!

This one might sound a bit crazy! But, indeed, I’ve observed this behavior in the large majority of teams I’ve worked with! User stories are great, but we want time for technical improvement! Here is a remedy that Michael Feathers shared during a training:

Always have a small backlog of small and precise refactoring tasks ready to be worked on.

We can work with the Scrum master to organize the grooming of a refactoring backlog. It needs to be small and visible!

Time for a change!

Are developers losing the planning poker game in the team you are working with? Here is what you can do:

- Present the average and previous sprint velocity strategies to the Scrum Master. Take the time to discuss the matter in-depth, and share the references from this article.

- Together, present to the team and discuss how to move to the previous sprint velocity strategy.

- Help the team to negotiate with the Product Owner. Suggest ways to ease the change. For example, the team might run an experiment over a few sprints. It could also gradually reduce the duration over which the velocity is averaged.

- Don’t forget to watch out for Parkinson’s law and scope creep!

I would love to read about your own developer tricks to pitfalls around Scrum Velocity! The comment section is yours.

Here are other posts about how developers can get more time for technical work:

- Leverage Scrum to workaround feature-factory sprint planning presents other Scrum-Aïkido techniques to take more time on technical excellence

- 5 Whole-Team Workshops To Increase Developers’ Role In Sprint Planning

- How to coach developers to get a chat with their product experts

- Make Testing Legacy Code Viral: Mikado Method and Test Data Builders presents a low investment, long-term, but viral way to inject testing in a legacy codebase

- How to convince your business of sponsoring a large scale refactoring

Leave a comment