Speed up the TDD feedback loop with better assertion messages

There is a rather widespread TDD practice to have a single assertion per test. The goal is to have faster feedback loop while coding. When a test fails, it can be for a single reason, making the diagnostic faster.

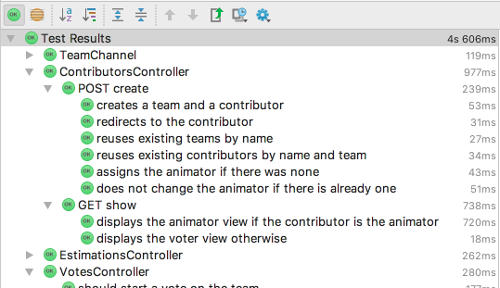

The same goes with the test names. When a test fails, a readable test name in the report simplifies the diagnostic. Some testing frameworks allow the use of plain strings as test names. In others, people use underscores instead of CamelCase in test names.

A 4th step in TDD: Fail, Fail better, Pass, Refactor

First, make it fail

Everyone knows that Test Driven Development starts by making the test fail. Let me illustrate why.

A few years ago, I was working on a C# project. We were using TDD and NUnit. At some point, while working on a story, I forgot to make my latest test fail. I wrote some code to pass this test, I ran the tests, and they were green. When I was almost done, I tried to plug all the parts together, but nothing was working. I had to start the debugger to understand what was going wrong. At first, I could not understand why the exact thing I had unit tested earlier was now broken. After more investigation I discovered that I had forgotten to make my test public. NUnit only runs public tests …

If I had made sure my test was failing, I would have spotted straightaway that it was not ran.

Then make it fail … better !

I lived the same kind of story with wrong failures many times. The test fails, but for a bad reason. I move on to implement the code to fix it … but it still does not pass ! Only then do I check the error message and discover the real thing to fix. Again, it’s a transgression to baby steps and to the YAGNI principle. If the tests is small, that might not be too much of an issue. But it can be if the test is big, or if the real fix deprecates all the premature work.

Strive for explicit error message

The idea is to make sure to have good enough error messages before moving on to the “pass” step.

There’s nothing groundbreaking about this practice. It’s not a step as explicit as the other 3 steps of TDD. The first place I read about this idea was in Growing Object Oriented Software Guided By Tests.

How to improve your messages

Readable code

Some test frameworks print out the failed assertion code to the test failure report. Others, especially in dynamic languages, use the assertion code itself to deduce an error message. If your test code is readable enough, your error messages might be as well !

For example, with Ruby RSpec testing framework :

it "must have an ending" do

expect(Vote.new(team: @daltons)).to be_valid

end

Yield the following error :

expected #<Vote ...> to be valid, but got errors: Ending can't be blank

Pass in a message argument

Sometimes, readable code is not enough to provide good messages. All testing frameworks I know provide some way to pass in a custom error message. That’s often a cheap and straightforward way to clarify your test reports.

it "should not render anything" do

post_create

expect(response.code).to eq(HTTP::Status::OK.to_s),

"expected the post to succeed, but got http status #{response.code}"

end

Yields

expected the post to succeed, but got http status 204

Define your own matchers

The drawback with explicit error message is that they harm code readability. If this becomes too much of an issue, one last solution is the use of test matchers. A test matcher is a class encapsulating assertion code. The test framework provides a fluent api to bind a matcher with the actual and expected values. Almost all test framework support some flavor of these. If not, or if you want more, there are libraries that do :

- AssertJ is a fluent assertion library for Java. You can easily extend it with your own assertions (ie. matchers)

- NFluent is the same thing for .Net.

As an example, in a past side project, I defined an include_all rspec matcher that verifies that many elements are present in a collection. It can be used that way :

expect(items).to include_all(["Tomatoes", "Bananas", "Potatoes"])

It yields error messages like

["Bananas", "Potatoes"] are missing

A custom matcher is more work, but it provides both readable code and clean error messages.

Other good points of matchers

Like any of these 3 tactics, matchers provide better error messages. Explicit error messages, in turn, speed up the diagnostic on regression. In the end, faster diagnostic means easier maintenance.

But there’s more awesomness in custom test matchers !

Adaptive error messages

In a custom matcher, you have to write code to generate the error message. This means we can add logic there ! It’s an opportunity to build more detailed error messages.

This can be particularly useful when testing recursive (tree-like) structures. A few years ago, I wrote an rspec matcher library called xpath-specs. It checks html views for the presence of recursive XPath. Instead of printing

Could not find //table[@id="grades"]//span[text()='Joe'] in ...

It will print

Could find //table[@id="grades"] but not //table[@id="grades"]//span[text()='Joe'] in ...

(BTW, I’m still wondering if testing views this way is a good idea …)

Test code reuse

One of the purpose of custom test matchers is to be reusable. That’s a good place to factorize assertion code. It is both more readable and more organized than extracting an assertion method.

Better coverage

I noticed that custom matcher have a psychological effect on test coverage ! A matcher is a place to share assertion code. Adding thorough assertions seems legitimate, contrary to repeating them inline.

Avoids mocking

We often resort to mocks instead of side effect tests because it’s a lot shorter. A custom matcher encapsulates the assertion code. It makes it OK to use a few assertions to test for side effects, which is usually preferable to mocking.

For example, here is a matcher that checks that our remote service API received the correct calls, without doing any mocking.

RSpec::Matchers.define :have_received_order do |cart, credentials|

match do |api|

not api.nil? and

api.login == credentials.email and

api.password == credentials.password and

cart.lines.all? do |cart_line|

cart.content.include?(cart_line.item.remote_id)

end

end

failure_message do |api|

"expected #{api.inspect} to have received order #{cart.inspect} from #{credentials}"

end

end

Care about error messages

Providing good error messages is a small effort compared to unit testing in general. At the same time, it speeds up the feedback loop, both while coding and during later maintenance. Imagine how easier it would be to analyze and fix regressions if they all had clear error messages !

Spread the word ! Leave comments in code reviews, demo the practice to your pair buddy. Prepare a team coding dojo about custom assertion matchers. Discuss the issue in a retro !

Leave a comment